As the COVID-19 pandemic has evolved, so have scientific opinions concerning infection risk. Because the virus was initially thought to be primarily transmitted by surface contact, masks were not recommended. The global supply of alcohol-based sanitizers was quickly depleted. Distilleries retooled to produce hand sanitizer instead of whiskey. Ironically, whiskey may have been more useful. Now it is clear that the virus is transmitted primarily, if not almost exclusively, by the inhalation of infected droplets and aerosolized particles in indoor spaces.

The infection rate has begun to drop, probably because of both the effects of effective public health messages and the increasing effects of vaccinations. Churches and universities are beginning to reopen, and organists, who have been largely relegated to Zoom, are beginning to return to an environment that may involve being in an enclosed space with other individuals.

Don’t be fooled, though. Even though buildings are reopening, the risk of COVID-19 is still very real. It is still a very dangerous disease with risks of long-term complications and death. It is still infectious–in fact, increasingly infectious with the rise of variant strains. Let’s take a look at how an organist can return to work safely.

Strategies to avoid infection

There are only three effective strategies to avoid contracting COVID-19: isolation, vaccination, and the proper use of effective masks. Organists, along with everybody else, should be vaccinated as soon as they can be. There is virtually no reason not to. It’s protective against infection and serious illness, and each vaccination will contribute toward defeating the pandemic. However, until sufficient numbers are immune, we will be wearing masks. Which masks we purchase and how we wear them could well determine the difference between life and death.

Masks are not created equal

It is probably true that any mask is better than no mask. Thin cloth masks that do not fit well probably still contribute to the safety of others in a room; however, they probably offer virtually no protection to the wearer. Cloth masks with multiple layers are better, but if they do not have an embedded wire to seal the mask around the nose, they are still not a good choice. An effective mask has to have enough layers to filter small droplets, and it has to fit well enough to prevent the exchange of gas around the edges of the mask. If you’re wearing a mask, you also need to breathe through the mask. If you can feel air escaping around your nose or around the edges of the mask, it is not protecting you, though again, it is probably still reducing the risk to those around you. Do not be fooled into thinking that you are safe if you go into a room with other people while wearing a thin cloth mask without a nose bridge.

The best masks are N95 masks. They filter at least 95% of airborne particles. However, they are also in short supply and still recommended only in healthcare settings. The best alternative is a KN95 mask. It meets the same standard as N95, but primarily in China. They were also initially depleted, but now are readily available on Amazon for $1 each. It is not necessary to use a new one for every occasion. They can be used unless damaged or until they no longer fit properly. You have to be a careful shopper, of course. There are counterfeit KN95 masks, but there are counterfeit N95 masks as well. The CDC has published an article providing guidance on the purchase of foreign masks. In addition, there are numerous reviews of masks on Amazon. If you’re going to be in a room with others, buy a real mask and wear it, and ask others to do the same.

Where are the risks?

Organs are mostly indoors. Therefore organists are mostly indoors. However, if attending an outdoor meeting or talking on the street, you have little to worry about as long as you maintain distance. There is almost no documented transmission of the virus in outdoor settings. Even the large recent outdoor demonstrations did not lead to a spike in transmission. If you get into a heated argument with a parishioner, yelling with your faces inches apart, you would be advised to wear a mask. However, keep in mind that you shouldn’t be getting into such situations in the first place.

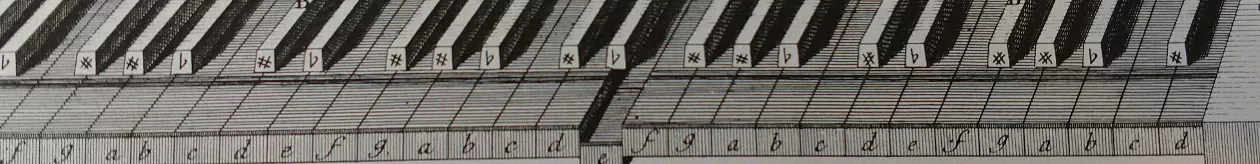

Can you catch the virus from a toilet seat? Probably not except for unusual circumstances that are beyond the scope of this publication. How about from the door handle on your way in? From an organ keyboard? Again, time has demonstrated that the risk is very low. There is almost no documented transmission of the virus from surfaces, if any. In an article in The Lancet in July 2020, Emanuel Goldman pointed out that the risk of surface transmission was exaggerated. Subsequent articles, in particular, a paper by Australian researchers, became tabloid fodder as they appeared to demonstrate a prolonged risk of catching the virus from any number of surfaces. The predicted glut of infections from surfaces did not happen, however. In a recent article in The Atlantic entitled “Hygiene Theater is Still a Huge Waste of Time,” Goldman is quoted describing the Australian paper as a “greatest-hits compilation of research errors.” An editorial this month in Nature reiterates the idea that we are foolishly directing resources on “deep cleaning” when those resources would be better applied to vaccinations, ventilation, and masks.

The risk for organists (and almost everybody else) is being in an indoor space with others. The social distancing recommendation of six feet may be effective for large droplets, but it is known to be irrelevant for aerosolized particles. Aerosolized particles spread quickly throughout a room and can remain there for hours. Cigarette smoke is also composed of small particles carried through the air. Though the comparison is not exact, it is helpful to think about cigarette smoke when evaluating the risk of aerosolized particles. If you’re sitting in a church, properly socially distanced at six feet, and the closest person to you lit a cigarette, do you think you would smell it? You could also inhale aerosolized droplets expelled by that person as a result of coughing due to a viral infection (and smoking!). An N95 or KN95 mask, worn effectively, substantially reduces, but does not eliminate the risk. A cloth mask that leaves gaps around the nose does not.

What’s an organist to do?

Practicing alone in a closed church carries very low risk. If you’re practicing after other people have recently been in the room, you might consider waiting an hour or wearing your newly purchased KN95 mask to further reduce the risk of inhaling a residual aerosolized droplet. If the previous organist coughed on middle C 100 times (an analogy inspired by the previously referenced Atlantic article), you come in a few minutes later and begin to play Passacaglia in C Minor, but take a break to pick your nose, you might just inoculate yourself. However, again, you shouldn’t be doing that anyway. Use a Kleenex. Wash your hands after you practice.

Meetings and church services up the risk considerably because they involve being with others in an indoor space. Still, you can take precautions to protect yourself and others. Wear your KN95 mask. You might also consider mask education for attendees. There appears to be no general public understanding that masks offer varying degrees of protection depending on their composition and how they’re worn. Even in the CDC’s recent requirement to wear masks on public transportation there is no real description of an effective mask except to say that it has to cover the nose and mouth. You might consider including a mask requirement in meeting notices stating that effective masks be purchased and worn at all times, without exception, in accordance with the guidelines published by the CDC.

Finally, what about choirs and congregational singing? The short answer is don’t do it. The idea that singers are safe without masks as long as they are separated by six feet is absurd. There is no way to make singing safe at this time; it should not resume until the pandemic is over. Asking people if they have symptoms is not effective; many infected persons spread the virus before they have symptoms. Taking temperatures has also been shown to be an ineffective screening tool. If you haven’t figured it out already, deep cleaning the choir loft is a waste of time. If, however, your job requires you to go into an indoor space where people are singing, remember that your new KN95 mask is your friend. If worn correctly and consistently, it should provide adequate protection from that coughing tenor.

The author is an organist, a retired physician, and Secretary of the Tacoma Chapter of the American Guild of Organists.